News

Incandescent Sublimity Against the Abyss: The Art of Ori Solomon Sherman, 1934-1988

October 11, 2022

By Leora Lev

Ori Solomon Sherman’s artistry is one of searing originality, the creation of oracular visions wrought of jeweled colors and the lights that his name signifies in Hebrew–“my light,” his mother exclaimed upon his birth–but irreducible to any single aesthetic movement, tradition, or medium. Sherman’s work is nourished by Jewish philosophical, spiritual, and poetic traditions and motifs, medieval European as well as Near Eastern manuscript illuminations, and marriage documents or ketubbot from “Italy in the age of the Ghetto to elaborately patterned Persian varieties” (Dobbs, 1987), but also by autobiographical components of an uncompromisingly honest and unique life. Born in Jerusalem, 1934, to observant Jewish parents Earl and Anna Sherman, and moving to New York City in 1936, Sherman absorbed the greatest Biblical, prophetic, and exegetical works (e.g. the Tanach, Talmud, Pirkei Avot, Psalms) of Jewish learning. He attained fluency in Hebrew through rigorous Hebrew school attendance, summers at Camp Massad—an American children’s camp where only Hebrew was spoken, created as the Shoah was transpiring—and tutelage from his mother Anna Sherman, a Hebraist and pioneering early woman Hebrew instructor at the Jewish Theological Seminary. Simultaneously, his early artistic proclivities blossomed with childhood training at the Museum of Modern Art, New York City’s venerable High School of Music and Art, and the Rhode Island School of Design, where he attended with full scholarship and became a prize-winning student, graduating in 1955. Sherman studied textile design, learning first from Anna Sherman, and then at RISD; an art that he would later enlist in mature works such as the multimedia tapestry “Adam and Eve” (1965). He also immersed himself in heterogeneous global traditions and techniques of painting, gouache, watercolor, ink, charcoal, woodblock engraving, woodwork, and Hebrew calligraphy.

After army service in 1958, Sherman moved to San Francisco, where his work at the renowned art frame store Gumps enhanced his mastery of decorative techniques such as application of metal leaf to wood, and “flat, bright, quick-drying casein colors used on frames… [which] paralleled the flat and brilliant gouache colors that he used in his artworks” (Dobbs, 1987). Fulfilling his polymath artistic proclivities, Sherman created a vibrant body of artworks in different mediums, as well as a spectrum of Jewish ritual objects such as ketubbot, dreidls, matzoh boxes, Kiddush cups, tzedaqah (charity) boxes, Yayin (wine) containers, Purim masks, and finely ornamented framed mirrors, furniture, and embroideries.

Within Sherman’s work, the Beast’s domain of annihilation is opposed by luminous traceries, wunderkammern that vividly re-imagine Jewish lives and histories, as well as those of his San Francisco community, and global brothers and sisters.

Sherman’s passion for the rich colors and exquisite detailing of medieval and Near Eastern illuminations, and ketubbot dating back to 440 B.C.E., continued to flourish with his mastery of Hebrew calligraphy, which had inscribed ketubbot “for the first time in the book of Tobit in the Apocrypha, becoming ubiquitous in the Babylonian exile” (Dobbs, 1987). But Sherman’s storied life also shaped his artwork. His gouache “Caesar’s Garden,” featured in the 1971 group exhibit and catalogue “Visions of Elsewhere” at the San Francisco Art Institute, enlists sophisticated scrolling ornamentation to evoke what might be a wondrously queer Gan Eden. Here, Hebrew characters become image, as primordial word had become thing, spelling the enigmatic phrase “there is no stranger in Caesar’s garden.” Eden’s originary man and woman are surrounded by strikingly stylized flora, and fauna rendered with homoerotic resonances. Oneiric variations of the Caesar’s garden trope; hermaphroditic deities; high-heeled fauns and satyrs resembling Sherman; a series of works in charcoal, gouache, and paint entitled “End of the Affair (Michael),” depicting male figures in extremis, with allusions to the expulsion from the Gan Eden but by leopard deities, accompanied by verses from the most lyrical erotic poem cycle of all, the “Song of Solomon,” figure in Sherman’s imaginative world. Sherman’s collaboration with poet Leland Mellott on the “The Men of Castro Village” (1981), with a gouache print, invokes both Biblical depictions of oceanic chaos and the free-floating amour fou of countercultural life in San Francisco before the AIDS plague. An aquatic, Surreal grouping of men, sea creatures, wild tides, and tugboat, with stylistic allusions to medieval woodblock engraving, complements Mellott’s ode to Castro’s homoerotic vitality.

Sherman’s honing of an original artistry of ketubbot garnered increasing private commissions and shows, culminating in the solo exhibit “Illuminations: The Artistry of Ori Sherman,” at the Jewish Community Museum in San Francisco, curated by Stephen Dobbs, who also wrote the catalogue’s excellent essay (1987). Sherman continued to produce visionary art in heterogeneous mediums, enlisting a Hebrew calligraphy of fiery letters to create worlds steeped in Jewish tradition but also colored with hues of personal experience. Phantasmagoric creatures, and flora with both mythological and Biblical resonances, but ultimately summoned from the shadow theater of his transformative imagination, fill his visual topographies. His twin brother Ari Joshua Sherman, whose first name means “lion” in Hebrew, frequently appears as that creature, in “Twins” (gouache, 1969), or in human form within intricate, mirror-image, point-counterpoint woodblock-like works such as “Twin Mandala” (1975).

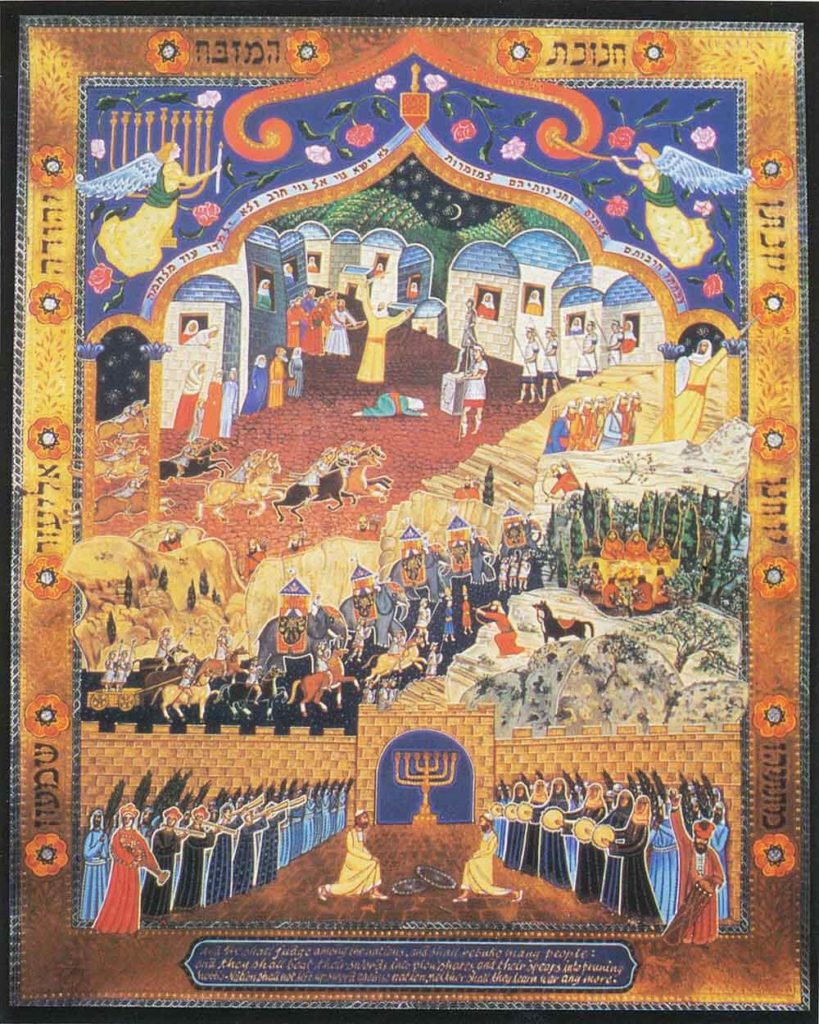

Sherman’s depictions of Jewish holidays in their layered beauty, rendered with vibrant singularity, would be published as The Story of Chanukah and The Four Questions with beautiful texts by Amy Ehrlich and Lynne Sharon Schwartz (both by Dial Press, 1989). But alongside this celebratory tenor is a darker skein featuring images of Malach Hamavet (the Angel of Death), as in the charcoal work “Cloaked Death” (1960); and the Shoah. The gouache work “1939” stages a Babel tower violating a female figure, as serpents and sinister jesters observe from balconies be-clouded by swastikas; the complicity of the Destroyers’ gaze is further reinforced by atavistic beast masks ogling this spectacle from the artwork’s outer frame. “Holocaust” (gouache, 1976) shows a lion of slavering maw, the ravening beast within flames of destruction revealing skulls that signify Malach Hamavet, or perhaps the sole remains after the process described by Primo Levi in If this Is a Man (1959). Above the furnace, against an azure backdrop, a frail, golden structure of two skeletal arms, surmounted by human hands that form the Hamsa symbol, houses the calligraphic Hebrew words “Ani Maamin” – “I believe.” These words, at the core of a nigun (or melody) believed to have been created by a Polish cantor in a wagon headed toward Auschwitz, were chanted by many Jews on their journey to the place of annihilation; a spiritual and Existential contestation of this Disappearing.

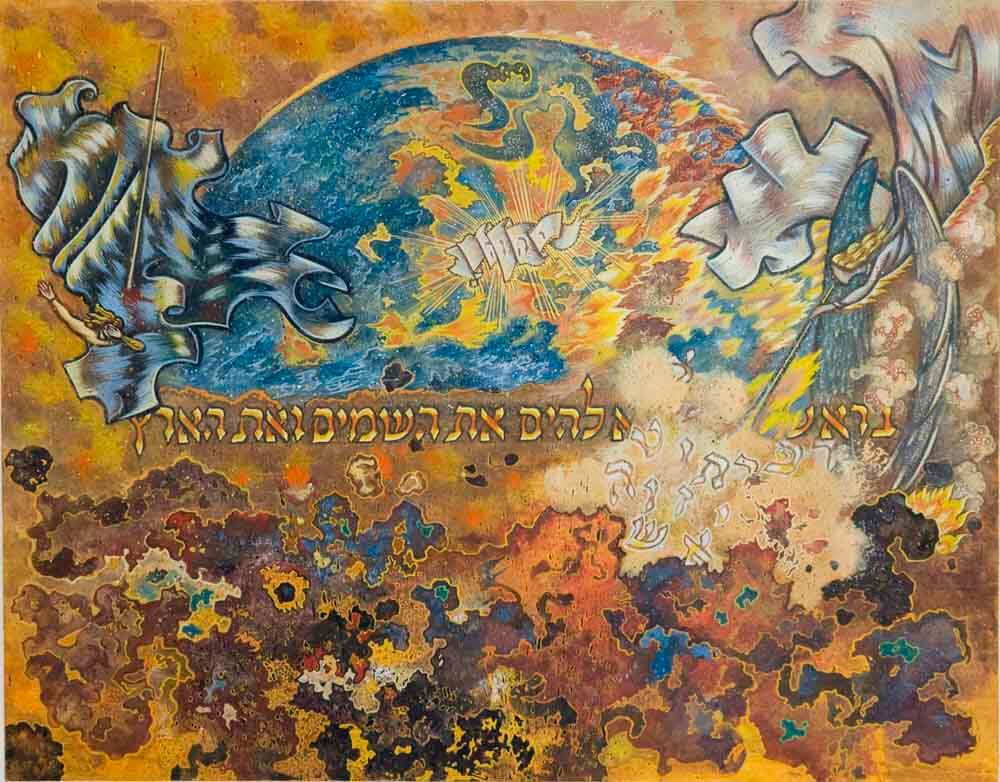

Mature works such as the “Celestial City” (c. mid 1980s) pair depict, in gouache, Jerusalem by day and night, hovering between a heaven and earth swirling with primordial clouds and fiery angels of Biblical and Blakeian resonance, but also a uniquely rendered numinosity that would later illuminate the Creation series. Sherman often signed his works with his Hebrew initials, Aleph and Shin, which in Hebrew spell fire or אש.

Ori Sherman died of AIDS in 1988. During his final year, he produced some of his most extraordinary work. He rendered the story of the Creation as told in the beginning of Genesis, enlisting Hebrew calligraphy, populating the Maker’s world with creatures wrought of beauty, flame, fearful symmetries, nephesh (soul) and will. Simultaneously, he created haunting pen and ink gouache illustrations of the very virus that was killing him, his beloved community, and the earth’s multitudes, for one of the first comprehensive books on AIDS (published posthumously, eds. Inge B. Corless and Mary Pittman-Lindeman, 1989). During his final months, he thus created the Creation itself, as well as its antithesis, the Plague, which he transmuted into art, with images that dared to imagine a Plague-free future. The AIDS virus is a dragon in a test tube; humanity joins together to fell the monster; black and white human figures ravaged by the disease nonetheless form intimate mandala patterns of solidarity, with the aesthetic and existential power of deepest grief and transcendent love. And amidst the works found by his sister Mrs. Varda Lev, after Sherman’s death, was an entire booklet of illustrations for the last Passover seder song, the Aramaic “Chad Gadya,” which begins with the slaughter of the innocent baby goat by Father for two zuzim, and ends with Ha Kadosh BaruchHu (the Holy One Blessed Be He), whose power transcends even that of Malach Hamavet, the Angel of Death, whom he slays.

Sherman’s work is a uniquely imaginative cri de coeur nourished by Jewish cultural rituals and aesthetic traditions, but also decrying the stultification of artistic, social, and communal conventions. It is a bright paean to Jewish life and existential vicissitudes, its timeless chagim (holidays), but also a mourner’s Kaddish for vanished Jewish worlds. Likewise, the work trembles with both the ecstasy and tragic eclipse of gay life, liaisons, and self-expression. The Shoah and the 20th century AIDS Plague reflect and refract each other in his work, unencompassable losses, the Catastrophe, the Beast, an absence, a gutting, a mourning, a howl. The zero degree point of annihilation exists in correspondance with the Celestial City, Yerushalayim shel zahav, Jerusalem of gold. The ebullient rendering of Jewish tradition, teeming with profound ritual, in enamel, paint, gold leaf, gouache, watercolor, ink, and stitching, on canvas, wood, paper, parchment, and tapestry, is the embroidery of a people’s multicolored, multilayered history; this counters the massed Tallitim (prayer shawls) and sacred memorabilia that line the mausoleum of mourning within the Jewish cultural imaginary, all metonyms for the mountains of extinguished bodies.

Within Sherman’s work, the Beast’s domain of annihilation is opposed by luminous traceries, wunderkammern that vividly re-imagine Jewish lives and histories, as well as those of his San Francisco community, and global brothers and sisters. Likewise, calligraphic Hebrew characters become form—as Jean Cocteau said that line and image exist in va-et-vient—in aesthetic collusions that mirror the entwining of Jewish tradition with worlds of fantastical fauna and fauna; the new life of Adam and Eve amidst the rush of the four Biblical rivers, but also queer male bodies in a Gan Eden of both meticulous and flamboyant flourishes; festive, transgressive arabesques. The light of this Garden is precious but precarious, shadowed by the threat of erasure. This is evident in so many visual dialogues within the tropes and stylistic innovations of his works, but, most poignantly, his rendering, during his final year of life, of both the Creation itself, and of the very Plague that was undoing him, his loved ones at home and globally. A Plague that he challenged with art, compassion, and the bravery to bring into being a wrenching vision of hope.

About the author

Leora Lev holds a PhD in Romance Languages and Literatures from Harvard, and teaches comparative literatures and arts at Bridgewater State University in greater Boston, where she is Professor, and art history in the Paris ISA Fine Arts Program. She has published and lectured internationally on European art, film, and fiction, with an emphasis on avant-gardes in relation to Nazism and Francoism; artistic tropes of monstrosity vis-a-vis psychocultural trauma; and the memorializing of Holocaust artists through cultural spaces that celebrate or elide national and personal histories. She interviewed John Waters for her book on transgressive art, which also includes work by Bay area luminaries, and collaborated on text-image exhibits with artists of queerness and creative iconoclasm.

Citations and Selected Ori Sherman Bibliography

Visions of Elsewhere, 1971. Exhibit catalogue for the San Francisco Art Institute’s eponymous exhibit, Spring 1971.

The Men of Castro Village, art by Ori Sherman, poem by Leland Mellott. Snow and Horses Press, 1980. Printed and typeset by the West Coast Print Center, Berkeley, CA., in a limited First Edition of 500 copies.

Illuminations: The Artistry of Ori Sherman, with Mark Dobbs, Jewish Community Museum, San Francisco, 1987.

The Four Questions. Art by Ori Sherman, text by Lynne Sharon Schwartz. New York: Dial Books, 1989; reissued, in hard copy, digital, and audiovisual format with images accompanied by English and Hebrew text read aloud. Levine Querido, 2021.

The Story of Chanukah, art by Ori Sherman, text by Amy Ehrlich. New York: Dial Books 1989.

AIDS: Principles, Practices, and Politics, illustrations by Ori Sherman, eds. Inge B. Corless and Mary Pittman-Lindeman. New York and London: Hemisphere Publishing Corporation (Taylor and Francis Group), 1989.

The Creation. Art by Ori Sherman, text by Stephen Mitchell. New York: Dial Books, 1990. Reissue: Levine, Querido, 2021.

Commemoration: “AIDS at 25: The Remembering Continues,” San Francisco Chronicle, Steve Winn, Jan. 8, 2006.

Latest News

Keep Up-To-Date